Hello from Oakland!

We’re sorry this update is late

We’re really sorry for the delay in this update. Since China was closed for business for about 3 weeks after our January update, we figured we were going to devote the February update to writing about the Model 01’s software. We also thought that we were going to send that update just before Jesse went back to Shenzhen at the end of February.

Time just got away from us a bit and we missed. Once Jesse was in Shenzhen, things were moving fast enough that we ended up deciding to delay until he was back home.

When the first half of this month’s update came in at more than 3500 words, we decided to split it in two. You should expect the second installment next week.

Schedule update

Right now, it’s looking like the first 100 units will come off the assembly line in early April. A few of those keyboards will be earmarked for things like FCC testing and taking marketing photos, but almost all of them are destined for Kickstarter backers.

The item that’s currently driving that date is fixing the insides of the keycaps. You can read a bit about that later in this update.

If everything looks good, that’s when we ask the factory to start mass production. Our current plan is for them to “batch” the production run into shipments of somewhere between 1000 and 2000 keyboards spaced 3-4 weeks apart. That helps make sure that if we do have an issue early on, we can resolve it quickly and easily. It also works well with the delivery schedules for our keyswitches, LEDs and wooden enclosures. We’ll talk more about the schedule in the second installment.

PVT

We mentioned on Twitter that Jesse was headed to Shenzhen to oversee preparations for PVT. Quite reasonably, someone asked what PVT was. “Production Verification Test”, also sometimes called the “pilot run” is when the factory makes a small part of your first production run using the final versions of parts on the assembly line.

In the software world, the closest analog would probably be the RC (release candidate).

The factory will make 100 Model 01s on the assembly line, using production parts. All the plastics come out of the injection molds. The PCBs are the final versions. The packaging is the final version, etc.

The idea is that it’s the time when they work all the kinks out of the production system. They make sure their assembly and test procedures are right and then we check their work. We ship out those 100 units as fast as we can to test the boxes and our shipping and delivery infrastructure.

The actual PVT run should only take a day.

The factory does their own internal QC, but It’ll probably take Jesse a few days to test all 100 of those keyboards.

As we go forward to Mass Production from there, we’ll have professional test folks checking the factory’s output. At first, they’ll check 100% of the keyboards. If the defect rate is close enough to zero, they’ll move to testing smaller and smaller percentages of keyboards until, hopefully, they’re just pulling out a few random units to check that the factory’s internal QC isn’t asleep at the wheel.

When Jesse got on the plane for Shenzhen at the end of last month, the factory thought there was a good chance PVT would happen before he came home. We didn’t really believe that, but it was a really nice fantasy to cling to for a few days.

IP Theft

It’s fairly common advice that if you make something that customers want, your product is going to get cloned by somebody with… flexible ethics. We’ve long maintained that we’re not too worried about the Model 01 getting copied by a “budget” manufacturer, as they’re exceedingly unlikely to copy the aspects of the design that you (and we) value the most—put another way: a crappy $30 copy of the Model 01 would amuse us a lot more than scare us.

Well, shortly before Jesse left for China, we got email from a Beijing law firm telling us that a Chinese company had registered for the “Keyboardio” trademark in China and asking if we’d like to pay them to fight it. This had all the hallmarks of a scam, so we ran it by our friends at HWTrek. They told us that they’d checked with some lawyers they know in Shenzhen and confirmed that yes, indeed, somebody in China was trying to register our trademark.

There’s a very specific scam that we think these folks were setting up. The way it works is that they register the trademark of a Western brand, hoping that nobody notices. Just as that company sends their first major shipment for export, the scammers ring up Chinese customs and tell them that there’s a Western company infringing on their legitimate trademark. They ask the customs agents to impound the goods shipped by that Western company. At this point, the law is very much on the side of the scammers. But there’s a simple, if costly, resolution. The scammers phone up the Western company and offer to sell them the trademark… for a moderately extortionary price.

Thankfully, this got caught early enough that we were able to file an opposition to the trademark filing. Our Chinese trademark lawyer tells us that the company who filed for our mark have also filed for over 100 other Western corporate brand names and that “the government really dislikes these guys.”

To oppose a trademark in China, you need to put together a packet of documentation showing that you were using the mark earlier than the date claimed by the other guys. In this case, the scammers claimed a first use of March 2016. Our guess is that they found out about us from this article in March 2016: https://www.toutiao.com/i6263004569421218305/

Of course, it could have been this article in 2015: http://tech.sina.com.cn/q/tech/2015-06-17/doc-ifxczqar0953559.shtml

Or this one in 2014: http://mouse.zol.com.cn/480/4805284.html

The documentation packet we ended up submitting included these articles, as well as a number of English-language pieces, our Kickstarter campaign, US Tax filings and some invoices and receipts with the corporate name on them dating from before March 2016.

When you submit a trademark opposition in China, you need to file for the mark at the same time. In total, this is about three times as expensive as just filing for an uncontested mark.

Thankfully, the total costs in China are still incredibly reasonable. The whole experience, including legal fees and all filing costs, came out to about USD 680. The amount is small enough that paying cash ended up being a whole lot more efficient than doing a wire. Since the document signing was done late in the day, the accounting folks were out of the office and the initial “receipt” was confirmed by IM. It was, of course, followed up by a formal receipt and a number of very official looking stamped documents.

We’ve filed our paperwork during the opposition period, so the trademark won’t be automatically issued. At this point, we don’t expect to hear about a formal result from Beijing before Q1 2018.

Paying lawyers in cash was definitely a new experience for us

Before writing about this, our lawyer confirmed that there was no danger to talking about it publicly.

Life lesson: If you’re a hardware startup and manufacturing in China, file for your trademarks in China before somebody else does. Even if you think you’re too little to be a target. It’s cheap and easy.

Keycap fit issues

One of the issues we’ve been going back and forth with the factory about is how tight the keycaps fit to the keyswitches. There’s a balance here: Too loose and the keycaps come out when you don’t want them to. Too tight and the keycaps take part of the keyswitches with them when you try to remove them. As of now, getting the keycaps right is the blocker for PVT.

Initially, the factory had recommended we go with their “regular standard.” When we asked, they said that the keycaps should require approximately 1 kg of force to pull off the switch. That’s a pretty normal number and we said we were fine with it. As the project moved forward, the factory revised their thinking. For a high-quality keyboard like ours, the keycaps should stay in a little better. They suggested that we switch to a 1.5 kg standard. We chatted with some friends who’ve made more of a study of keycaps than we have and, again, said we were cool with that.

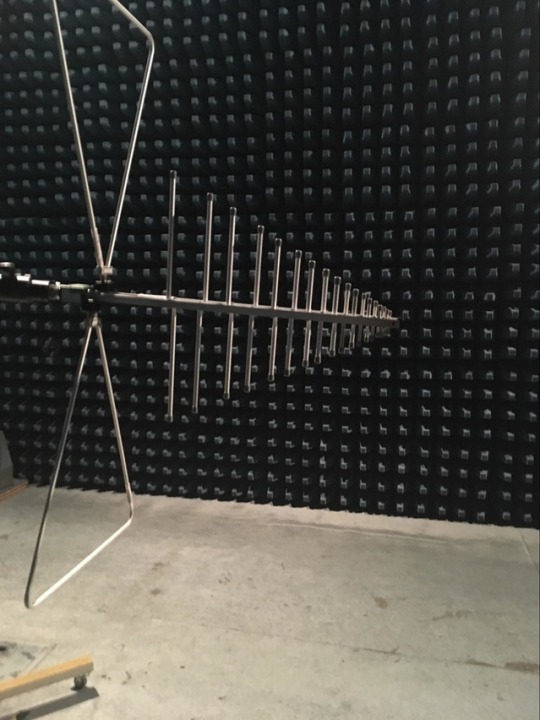

As sample keycaps came back from the factory, we found that they seemed to be rather difficult to remove from a keyboard. We asked the factory to have the keycap removal force measured. After some back and forth, we got a somewhat fuzzy report that none of the keycaps required less than 1.5 kg of force to remove.

Pushing a little harder, the factory agreed to have formal tests run to see how much force the keycaps really took to remove.

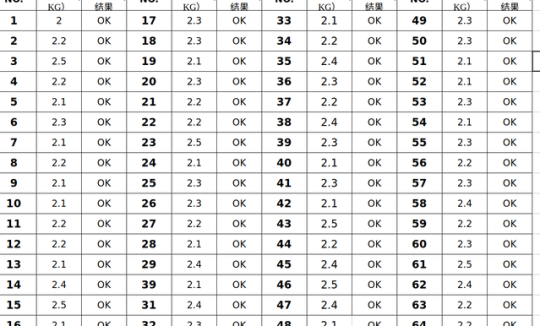

In this report of keycap removal force, when they say “OK”, they really mean “Not OK”

The report came back, saying that no keycap required less than 2.2 kg to remove, with some needing up to 2.5 kg of force. That report, combined with our confirmation that we were able to destroy keyswitches just pulling off keycaps made it clear to the factory that they were going to have to press the keycap factory to resolve this issue.

When we sat down with the keycap factory, they initially proposed asking our keyswitch vendor to change the switch design and then suggested modifying every keyswitch to make the keycap fit a bit less tight. We explained that those solutions weren’t going to work for us ;)

The solution, first designed by our factory’s R&D Manager and later confirmed by the keycap factory is to round the corners of the keycap stems, removing just a little bit plastic. We agreed that we could accept anything that required between 1 kg and 1.5 kg of force to remove.

The solution, while 100% correct, does have one pretty serious complication. The keycaps are injection molded. To make an injection molded part larger, you cut away a bit of the steel from the injection mold. To make an injection molded part smaller, you have to add steel to the injection mold. In this case, the way you do that is to cut a “plug” out of the injection mold and replace it with a precisely-sized replacement plug that has a bit more steel.

We all agreed that before modifying the entire injection mold, the keycap factory should get things right on a single keycap first. Doing this for a single keycap is about a 1-2 day job. Doing it for 64 keycaps is about a 2-3 week job.

We finally went and bought our own force gauge

Before Jesse left China, he saw the keycap factory’s first attempt, which took only 0.34 kg to remove.

The second attempt, which we didn’t get to test was reported to be just shy of 1 kg of force.

The night before he left China, Jesse saw their third attempt, which overshot slightly and took 1.6 kg to remove in our initial tests.

Last night, the factory said that the keycap supplier had delivered a sample keycap to them which requires 1.3Kg of force to remove. They’re happy with the result and have instructed the keycap vendor to modify the other 63 keycaps to match.

FCC/CE test lab

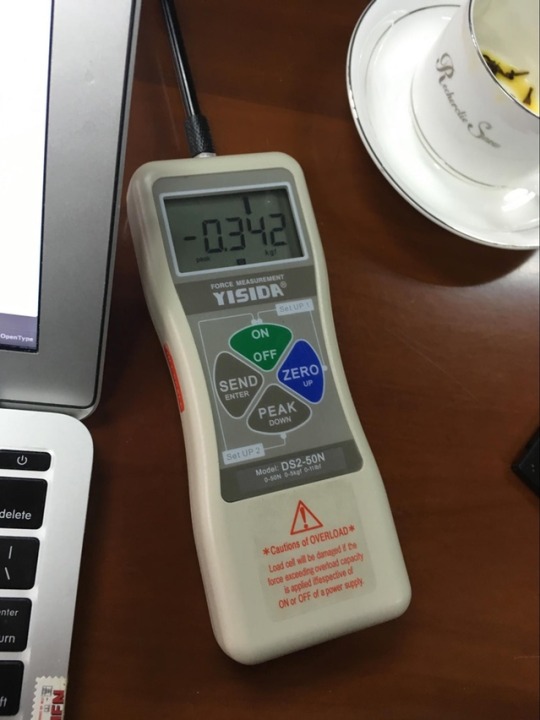

On the Friday before he left Shenzhen, Jesse visited the testing lab recommended by our manufacturer. These are the folks who will do the FCC and CE testing on the Model 01.

This is the antenna which will verify your Model 01 complies with Part 15b of the FCC rules

They also do reliability testing for a variety of products. We’ll likely end up using a few of their test offerings, including the “constant temperature” (baking) machines, the UV testing machines, and the “salt fog” (corrosion testing) machines.

The corrosion testing machines are used, mainly, to verify that the PCB isn’t going to to suffer catastrophic failure after spending 48 hours in a saline fog. We had to be clear with them that we know a wooden enclosure will not pass an intense corrosion test like this and that the results of the test on the enclosure would be informational only.

The 96 hour constant temperature test helps make sure that those of you in Arizona and Singapore aren’t in for a colossal disappointment.

The intense 96 hour UV aging test makes sure that the coatings on the keycaps and the enclosure aren’t going to start flaking off after a short period of time on your desk.

By far the coolest and scariest part of the test lab was their battery testing room. Some of their battery testing machines almost made us wish the Model 01 had a battery.

Sadly, the test lab wasn’t willing to show us what happens when a product fails a test on this machine

The current plan for FCC/CE testing is that our factory will work with the test lab to perform “pretesting” with hand-assembled prototypes. These tests are a tiny bit cheaper because the testing lab isn’t certifying their results and nothing is being “officially” signed off. But they’ll let us catch potential issues before it’s too late.

Once we have PVT units assembled on the production line, a few will go to the test lab and start working their way through the formal test process.

We’re still doing our diligence on proper labeling and shipping requirements for PVT keyboards we ship before the formal FCC Declaration of Conformity from the lab—we want to make sure your keyboards don’t get held up by a zealous customs agent.

Screwdrivers

We mentioned in a previous update that the screwdrivers the factory had selected weren’t sized correctly to open the keyboard. When Jesse got to China, we talked about it with the factory and they said that they had a few ideas for screwdrivers, but didn’t have samples on hand yet. (While not our favorite answer, that’s entirely reasonable. Screwdrivers are a commodity item with relatively short lead times.)

The orange screwdriver we like, along with some samples provided by another vendor

Since he was a little bit antsy, Jesse reached out to a few screwdriver suppliers from Alibaba directly. He contacted 8 suppliers at 11:30PM on Friday night. The first three suppliers got back to him in well under an hour. Two of the suppliers offered to customize samples with our logo and promised to deliver the samples locally before Thursday, the day we’d arbitrarily selected to make our final choice. The third supplier said they couldn’t do a custom logo in less than a week, but that the sample would be free.

Sample fees are an easy way for vendors to help weed out folks who are just trying to get a single free copy of an item.

One vendor shipped us two laser-engraved orange screwdrivers for a sample fee of about $20. They arrived the following Monday.

Another shipped us five screwdrivers in a variety of colors, with samples of both Pad-printed logos and laser-engraved logos for a sample fee of about $20. They arrived on Thursday.

The third vendor shipped us a single screwdriver with another company’s logo on it (as we’d agreed). The sample was free, but they didn’t tell us that shipping would be COD until after the sample was on its way.

In the end, we liked orange sample the best.

Based on this, our factory say they want to try one more vendor. We’re pretty happy with what we’ve got, but we’ll have a look at their sample too.

Packaging

We’ve been talking to the factory about packaging for a long time. We had a detailed packaging spec in our original RFQ (request for quotation).

A preview of what your unboxing experience might look like

The first packaging supplier the factory brought in were… not great at meeting their self-imposed deadlines. They got us a first sample, but didn’t really deliver a proposal. We showed some photographs of this sample months ago. Eventually, they failed to deliver promised updates one-too-many times.

While in China, Jesse worked with two packaging suppliers introduced by the factory and one supplier introduced by a friend. The experiences couldn’t have been more different.

The supplier introduced by a friend is… very high end. We tried to get them to spec two versions of the packaging—one a “cheap, but strong” box and the other showing off what they’re good at. Their inexpensive offering was really nice, but was an eye-popping $15.

Their nice offering? It was gorgeous. The slide-out drawer for the keyboard’s accessories had a silk ribbon. Describing it as out of our price range does a disservice to the word “understatement.”

We didn’t get a great vibe from the first packaging supplier introduced by the factory. They hadn’t really prepared for the meeting. We spent the better part of an hour talking about what kind of foam might make sense to use inside the box and getting a quick tour of their foam-cutting operation. Supposedly, they also do cardboard boxes, but at another facility. They don’t do printing, which we need for things like the manual and layout card. They promised to build up a sample, but we never saw it.

The second packaging supplier came to us for a first meeting before we visited them for the second meeting. At that first meeting, they brought an initial design for the cardboard box and the foam inserts. We talked through changes we wanted, as well as what we wanted for the keyboard’s manual and layout card. When Jesse asked what format they wanted the layout card and manual in, they asked for Adobe Illustrator (CS5). They actually asked about typefaces.

For the second meeting, we visited their factory in Dongguan. They’d made a second sample box incorporating most of the changes we’d talked about. They’d done a first mockup of the manual, cut in the shape of the keyboard. It was about 3cm x 5cm. The text was a little bit too small to read. We talked about it and Jesse explained that we’re not including the manual just because we have to—we actually want people to read the manual.

The sample of the layout card wasn’t quite right. We’d asked for something “laminated” and the first few things they came back with were plastic-coated, but still pretty easy to fold or tear in half. Eventually, we showed samples of restaurant menus. That got the idea across and before Jesse left China, the packaging factory delivered samples that were exactly what we’d been looking for.

Two years ago, we’d estimated the Model 01’s shipping weight at 5 pounds. We’ve used that estimate as part of all of our shipping calculations. We thought that number was relatively safe. But we never really knew. When we put the fully-loaded package on the scale in the packaging supplier’s conference room, it came out at 2.21Kg. That’s 4.87 pounds. That was a really happy moment, though we don’t think the factory or the packaging supplier understood why.

Simon-Claudius Wystrach (@thebaronhimself) is responsible for the layout card actually looking pretty. We based the style on a template designed by Arley McBlain (@arleym)

Before we left China, we saw two more revisions of the packaging, with further refinements. We were a little annoyed to see that the text on the back of the box at one point read “Design in Oakland, California” rather than “Designed in Oakland, California"… and more than a little embarrassed to realize that the issue was that they’d faithfully reproduced a typo Jesse made.

One of the last things to change was that the supplier rotated the orientation of the corrugation of the cardboard 90 degrees to help make sure that the little locking tab doesn’t fall apart as easily. It’s a tiny detail, but it’ll make the packaging just a little bit nicer.

But wait, there’s more!

That’s it for today, but watch for part two of this month’s update sometime next week. Things we’re planning to talk about in that post include: Long leadtime components, keycap painting and engraving, the new baseplates (which look great), the stands, the rails and center bars, the firmware, and a few other tidbits.

<3 j+k